I have found inspiration for this post in the newest book of Jaroslav Čechura who recently published the monograph titled Neklidné století: Třeboňsko v proměnách válečného věku (1590–1710), in translation Turbulent Century: Třeboň Region in the Changes of the War Age (1590–1710).

The monograph focuses on the period covering more than a hundred years which include also the inauspicious event of that time, the Thirty Years War. The author describes the turbulent events from the perspective of everyday life of farmers and peasants using various and varied sources surviving the SOA Třeboň. On the fates of specific actors, Čechura builds general patterns of behaviour of the then subjects and also of the administration of the estate. I can not recommend this book enough.

On pp.65–67 Čechura describes the damaging impact which the events of Thirty Years War had on the villages of Třeboň estate using the records from land books for villages Branná, Hrachoviště, Ševětín, and Vitín belonging to the Třeboň estate. I took the time to look up all the records for Branná referred to in the book to convey the impression.

To help you practise working with the Czech text, in addition to the translation, I also provide the transcription of the original language and a „translation“ into contemporary Czech.

Adamův grunt (Adam’s farm)

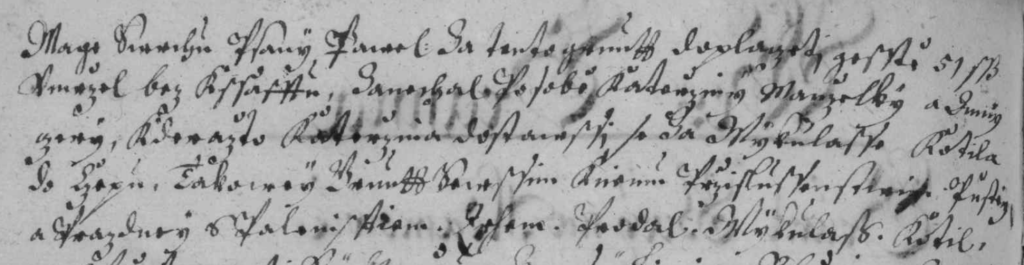

The last recorded annual payment made by Pavel, the possessor of the farm, was from Christmas 1617. Then follows this record from 1628:

Czech 1: Mage swrchu psany Pawel za tento grunth doplaczetj gesste 51 ß | umržel bez kssaftu, zanechal Po sobě Kateržiny manželky a Anny | czery, kderažto Kateržina dostawssi se za Mykulasse Kotila | do Cžapu, takowey Grunth se wssim k niemu Pržislussenstwim pusteg | a prazdney spalenisstiem trhem prodal Mikuláss Kotil […]

Czech 2: Maje svrchu psaný Pavel za tento grunt dopláceti ještě 51 ß | umřel bez kšaftu, zanechal po sobě Kateřiny manželky a Anny | dcery, kterážto Kateřina dostavši se za Mikuláše Kotila | do Cepu, takovej grunt se vším k němu příslušenstvím pustej | a prázdnej [s] spáleništěm trhem prodal Mikuláš Kotil[…]

English

Having yet the above written Pavel to pay 51 ß he died without a will and left behind him Katherine his wife and Anna his daughter. Kateřina getting [married] to Mikuláš Kotil in Cep, Mikuláš Kotil sold through purchase this grunt with all [belonging] accessories, desolate and empty, with a burnt ground.

Franteslův Grunt (Frantesl’s farm)

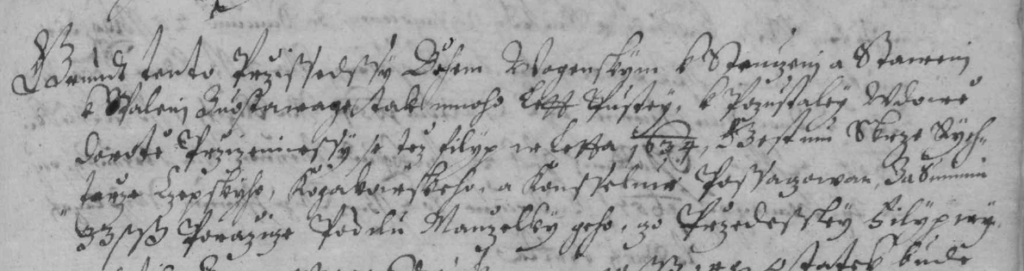

There is a gap in the records of annual payments for this farm as in the previous record. The last one recorded comes from 1617 when Filip Svízelka, then the possessor of this farm, laid down 4 ß. The next paragraph explains what happened in the following years:

Czech 1: Grundt tento Pržissedssy Během wogenskym k stenczenj a Stawenj | k spalenj zustawaje tak mnoho let pustey, k pozustaley wdowě | Dorotě Pržizeniwssy se tež Filyp w letta 1634 Gest mu skrze Rych- | tarže Czepskyho, kojakowskeho, a konsselma posssaczowan za Summu | 33 ß […]

Czech 2: Grunt tento přišedší během vojenským k ztenčení a stavení | k spálení zůstávaje tak mnoho let pustej, k pozůstalej vdově | Dorotě přeživší se též Filip v léta 1634. Jest mu skrze rych- | táře cepskýho, kojakovského a konšelama pošacován za sumu | 33 ß […]

English

This farm, which came to thinning and the buildings were burned down, remained desolate for many years. The [Filip’s] surviving widow married also Filip in the year 1634 the farm is appraised for him by the rychtáři (pl.) from Cep, Kojákovice and konšelé (pl.) for the sum of 33 ß

Tětíkův grunt (Tětík’s farm)

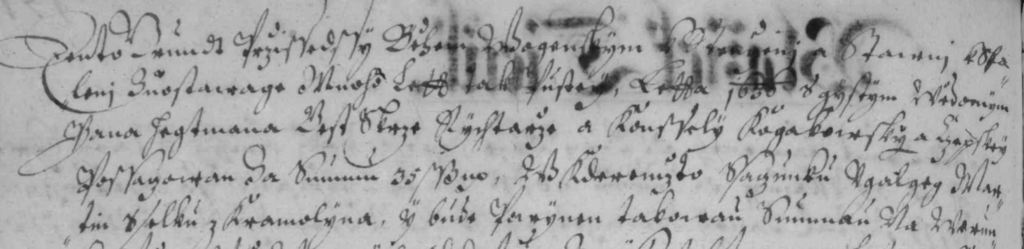

In 1605 Blažek Tětík paid his last instalment for his farm and thus finally paid all the claims tied to the farm. However, the recorded history of the farm continues only in 1636 when the farm was as deserted appraised and given to a new farmer:

Czech 1: Tento grundt Pržissedssy Během wogenskym k stencženj a stawenj k spa- | lenj zusatwage Mnoho Leh tak pustey, Letha 1636 s jystym wědomym | Pana hegtmana Gest skrzy Rychtarže a konssely kojakowsky a Czepskey | possaczowan za Summu 35 ß, w kderemžto ssaczunku ugal geg Mar-| tin SSelku z Kramolyna, […]

Czech 2: Tento grunt přišedší během vojenským k stenčení a stavení k spá-| lení, zůstavaje moho let tak pustej, léta 1636 s jistým vědomím | pana hejtmana jest skrze rychtáře a konšely kojakovské a cepský | pošacován za sumu 35 ß, v kterémžto šacunku ujal jej Mar- | tin Šelků z Kramolína , […]

English:

This farm, which came to thinning and the buildings were burned down, remained desolate for many years. In the year 1636 with a certain knowledge of Lord Hejtman, it is appraised by rychtáři and konšelé [pl.] of Kojákovice and Cep for sum 35 ß, for which appraisal Martin Šelků z Kramolína took it over […]

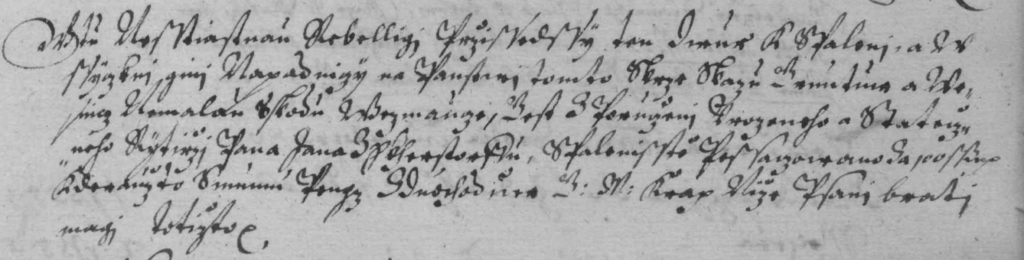

Statek dvořákovský (Dvořák’s farm)

Czech 1: W tu Nesstiastnau Rebelligi Pržissedssy ten dwur k spalenj a w- | ššiczknj ginj napadniczy na panstswi tomto skrze skazu gruntuw a we- | snicz nemalau škodu vezmaucze, Gest z porucžnj Urozeneho a Statecž- | neho Rytirži Pana Jan z Skherstowstu, spalenisstě possaczowano za 100 ß | kteraužto Summu pengz z duchoduw J. M. Kra. níže psanj bratj | magi totižto

Czech 2: V tu nešťastnou rebelii přišedší ten dvůr ke spálení a v- | šichni jiní nápadníci na panství tomto skrze zkázu gruntův a ve- | snic nemalou škodu vezmouce, jest z poručení urozeného a stateč- | ného rytíře pana Jan z Skehstorou, spáleniště pošsacováno za 100 ß, | kteroužto sumu peněz z důchodu J. M. Krá. níže psaní bratři bráti | mají, totižto

English:

In that unfortunate rebellion the farm came to be burned, and all the other claimants on this estate, through the destruction of farms and villages, took no small loss. [Therefore] by the command of a noble and valiant knight lord Jan z Skehstoru is the burned pace appraised for 100 ß, which sum of money the brothers below written are to take from the property of His Royal Grace, as follows

All four records are monotonous in their wording. In the first two records, there was a widow after the last recorded possessor of the farm who remarried and their new husbands either sold the farm or started to use it. Also, the third farm found its new possessor, yet in this case, there was not direct link to the previous farmer.

The entry for the fourth grunt is atypical. It comes from 1642 and it was not made on the occasion of the farm transfer to a new farmer. On the contrary, the farm continued to be abandoned. The steward of the estate at the time decided, as a special favour to heirs who were entitled to payments of their inheritance shares from the estate’s treasury, that part of their claims would be paid out of the royal assets (because the whole estate forfeited to the king and the crown was in charge of the Třeboň estate at that time).

The picture of the village is grim. Burn out places and waste land. In total, we could count four farms described as destroyed, devastated, and spoiled in Branná, a village with four recorded farms. The numerous military campaigns and marches, no matter to what warring party the soldiers belonged, brought disaster to the village. Their official, as well as unsanctioned requirements of the soldiers for accommodation and food, contributed to the destruction of this village. All this is not an extreme or solitary example of the recorded destruction for one unfortunate village. Such records are no exception and we would find many examples in this book and in other land books.

A caveat. Reality may not have been as bleak as our imagination portrays it. As the author reminds us (p. 105), the adjective „pustý“ (desolate) in the pre-1620 sources of Třeboň provenance admits a wider possible interpretation of the term. It is highly probable that the term „pustý“ meant primarily the equivalent of the contemporary term „barren“, overgrown with grass, uncultivated. But the word “pustý” could also mean empty, abandoned. The dual interpretation is based on the frequency of the word in the sources and the relevant context. Yet, when the reference is to a burnt place, the meaning is unambiguous. We must also admit that some unused fields were temporarily farmed by someone else who actually sowed and harvested fields and who was not a possessor of this farm.

What I like in this case is the greater picture which can be extracted from land books. In fact, it is something which we may miss easily. As genealogists or family historians, we are, of course, concentrating on a farm or a family which are important and interesting for us. Yet, we may thus lose the picture of the “big history” which we have right in front of our eyes.

ČECHURA, Jaroslav. Neklidné století: Třeboňsko v proměnách válečného věku (1590–1710). 1st edition. Praha: Univerzita Karlova, nakladatelství Karolinum, 2021. 413 pp. ISBN 978-80-246-4730-2.